I want find space that is empty.

Space that is not cluttered.

Space that is free from people.

“Space is both determines and is determined by the improvisation occurring within it, offering stimulation, limitation, location, orientation, motivation and more.”(De Spain, 2014, 108) My own habitual tendencies create limitations in space and thus determine my improvisation.

I know that I like large open spaces, I like to feel free, and I know in this type of space anything is possible.

I search and listen for space that is empty. I walk towards it… someone else arrives there first. Should I change or stick with my intention?

I know what habitual me would do, she would change her intention and would keep on doing so until she found that open space.

So I stick with my intention and now I am face to face with someone else.

The same happens again, my shoulder is touching someone else’s.

Through experimenting with space I have come to discover that restricted space is not as daunting as I imagined.

I will allow myself to experiment within restricted space, whether it is physical or mental.

“In improvisation, time can be friend or foe” (De Spain, 2014, 114)

Following Barbara Dilley’s improvisation practice, whilst dancing the improviser calls ‘out the beginning, middle, and end of the dance as they feel them arise as the piece unfolds’ (Buckwalter, 2010, 69-70).

In this case time is my foe.

- Beginning – I explore a small movement, a finger tapping against my leg. The size of the movement begins to gradually increase. When I have reached the point where I can increase the movement no more, the beginning is over.

- Middle – I feel the need to travel, initiating at first from the finger. I explore movement initiating from different parts of the body; the hip, the chest, the heel, the knee, the head, the elbow. I feel I have exhausted all possibilities, the middle is over.

- End – I begin to make my way to the floor, my effort level decreases dramatically. On my knees, I slide out my arm… END! My two minutes are up.

My foe did not allow me to find my ‘felt ending as signaled by the body or an organic ending that comes out of the material’ (Buckwalter, 2010, 60).

I will never know what would have happened in that moment. I can offer possibilities, but never know for certain. I cannot re-create everything that occurred within those two minutes.

Time is an interesting concept in improvisation. Two minutes can seem like two seconds. I have no sense of time when I’m improvising; I become absorbed in the moment and all its possibilities.

It all comes down to chance.

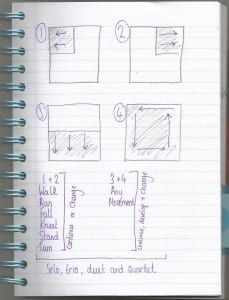

As a final task we were given a chance score, taken from the ideas of Nina Martin.The groupings and time in which the score would last were selected at random. There will be a solo, duet and a quartet. They must follow this order.

The score will last for 3 minutes.

All three sections will be performed within the time.

The people dancing within the groups does not have to stay the same.

This score allowed me to apply everything I have learnt in the past few weeks:

>I had to track not only my own movement but also others.

>I had to focus my attention on ‘the relationship and interaction of more than one “thing”.’ (De Spain, 2014, 168) Movement, time, space, contact and relationships.

> I did not have an intention, I did not create limitations.

> I had to be consciously aware of time, in order to fit all three sections within the three minutes.

> The space was open, we could determine what occurred within it.

After thought…

I have now been learning the art of improvisation for four weeks, combing the structures and modes of dance improvisation such as tracking, attention, intention, time and space into my improvisational practice has allowed me to gain deeper understanding of the practice and its concepts. I feel that I can apply all of these concept, that I have learnt so far, into improvisation.

I have engaged in improvisation from a number of starting points which range from throwing bean bags to paying attention to a particular body part. A starting point determines a lot within improvisation, it sets a tone and initiates an unconscious intention (whether that be a good or bad thing is questionable). I look forward to the coming weeks where starting points can be explored further.

Buckwalter, M. (2010) Composing While Dancing, An Improviser’s Companion. USA: University of Wisconsin Press.

De Spain, K. (2014) Landscape of the Now. New York: Oxford University Press.